Performance of an engineering manager

In one of my previous posts, I talked about performance quantification for IC engineers, and recently I’ve been thinking about whether we can map the same framework (or way of thinking?) to quantify engineering managers’ performance. Quantifying performance is always hard, and it is especially hard for engineering managers.

In High Output Management, the author’s primary point is that “a manager’s performance is measured not by individual output, but by the output of their entire organization and those influenced by them.” While this principle is often quoted, it oversimplifies the real-world complexity of management. I’ve seen cases where this idea fails to capture what’s really going on:

Failure patterns that break the model

- Hero-based success: A team delivers, but only because one or two individuals carry the load.

- Burnout-driven delivery: The team ships work, but at an unsustainable pace - while others are checked out or absent.

- Fearful delivery: The team delivers, but doesn’t feel safe giving upward feedback or being transparent.

- Toxic success: The manager is present but harmful - micromanaging, creating fear, or being absent and disengaged.

This gets even more complicated in modern companies, where people change jobs frequently (the average tenure is around 18 months in the industry). Managerial impact often takes time to compound. While the industry rewards mobility, the most meaningful management work - like coaching new leaders, shifting team culture, or stabilizing delivery - often requires longer horizons.

Even companies like GitLab have recognized this with their “longevity work requirement” for external candidates:

“External candidates with 5 or more years of experience should have at least one job with 2+ years of tenure where they were not self-employed or a ‘Founder’ from the past 5 years.”

This isn’t just about loyalty - it’s about showing you can stay long enough to drive and sustain change.

You’ll also see companies run yearly or biannual culture or management surveys. While useful, these often reveal only a fraction of reality = typically the safest 20%. Power dynamics, fear of retaliation, or survey fatigue distort what gets reported. That’s why pairing surveys with qualitative feedback, observable dynamics, and strong skip-level engagement is critical.

Rethinking input, output, outcome, and impact for managers

Let’s start with the averaged-out requirements of the job: hiring, retaining talent, performance management, delivery, and strategy.

When you zoom out from the mechanics of all these responsibilities, a pattern starts to emerge: in each of them, you can reason about input, output, outcome, and impact.

-

Input: Your effort and time. This includes 1:1s, coaching, planning, hiring loops, running retros, resolving team conflict, and emotional labor. Input is invisible unless you make it visible - but it’s the foundation of everything else.

-

Output: The tangible things you create. Strategy docs, performance plans, hiring decisions, onboarding plans, roadmaps, rituals, presentations - these are the artifacts of your management work.

-

Outcome: The effectiveness of your work. Did your new hire succeed? Did your growth plans help engineers get promoted? Did your team rituals lead to better delivery or less burnout? Outcomes tell us whether your output made a difference.

-

Impact: The lasting change you’ve created - often beyond your team. This might be new leaders you’ve grown, company-wide processes you’ve improved, or cultural shifts you’ve led. Impact is how your work compounds.

Concrete examples

Hiring

- Input: Interview plan, hiring committee, feedback loops you put together

- Output: Interview results, candidate feedback

- Outcome: Hired or not hired

- Impact: New team member joins, team velocity improves, long-term skills gap addressed

Performance management

- Input: Identifying low performance early, giving feedback

- Output: PIP or other support plans

- Outcome: Team member improves or exits

- Impact: Healthier team culture, higher engagement, fewer blockers

A performance formula for managers

Just like with ICs, a manager’s performance can be viewed as a weighted combination of these four dimensions:

Performance = w₁(Input) + w₂(Output) + w₃(Outcome) + w₄(Impact)

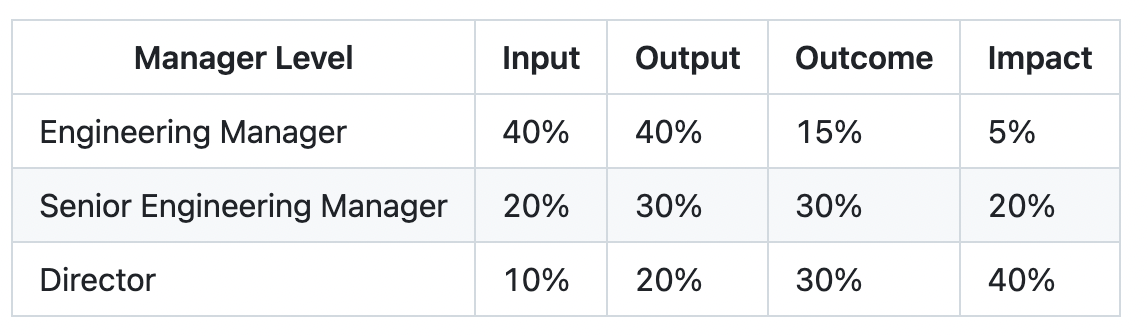

The weights shift based on your role and scope:

This framework helps clarify expectations and makes performance conversations less subjective.

Tracking and improving

The most effective managers I’ve worked with track their own progress weekly:

- What did I do that had lasting value?

- Where did I spend time but get no results?

- Did I create leverage for others?

Keeping a weekly log, even a short one, helps avoid surprises during review season. It also reveals patterns: Are you spending all your time unblocking, but not investing in long-term outcomes? Are you over-indexing on input and burning out?

Beware of false signals

Some managers might appear effective on paper - high delivery, positive survey scores, happy leadership. But if they:

- Avoid conflict or hard feedback

- Hoard decisions instead of creating leverage

- Burn out their team chasing short-term wins

…then the long-term impact may be harmful, even if the short-term metrics look great.

Final thoughts

Being a great manager isn’t about being the busiest, the loudest, or the most liked. It’s about being effective - creating the conditions where others can thrive, and where good decisions happen without you in the room.

By quantifying performance through Input, Output, Outcome, and Impact, we can build clarity, reduce bias, and have better conversations about what success actually looks like.

And perhaps most importantly: it reminds us to value the invisible work - because that’s where leadership lives.